In answer to Vinay's questions:

Loons and some cormorant species can stay underwater for a minute and a half. Some cormorants can stay under for over two minutes. It's quite a bit less than that for diving ducks and grebes. The hollow bones (and the huge amount of air they carry with them) definitely makes it hard for them to stay underwater. Most diving birds can compress their feathers flat against the sides of their bodies to eliminate any extra air.

The record for a human holding their breath underwater is over 19 minutes, but in that span of time the human is doing absolutely nothing. Diving birds, on the other hand, are doing a lot.

Diving ridiculously deep

Flying

Going really fast (watch the bubbles behind it as it surfaces)

Foraging

Or staying above water and winning the cuteness award.

Notice the different swimming styles of the birds. You can't see what's going on with the Imperial Cormorant's rear end, but it has the same way of swimming as the loon: it paddles with it's webbed hind feet. The murres (a type of alcid) flap their wings and steer with their feet. They're sort of the halfway point between flying birds and penguins; they compromise between flight and swimming.

Now take a close look at those grebes. Their feet do not have webbing; instead, each of the three toes is lobed and flattened. But that's only the beginning of the weirdness. What's it doing with those feet? Is it paddling with them? Only a little bit. If you look closely, it's not just waving them back and forth.

It's spinning them.

Recent research has shown that most of the swimming power in grebes comes not from pushing the water backwards like loons or humans, but by creating hydrodynamic lift similar to a boat propeller.

I love grebes.

Now on to the subject of larids:

I'm using this terminology a bit broadly. Technically, larids are only things in the genus Larus. But I needed a name shorter than "Gulls and their Allies" with which to refer to this group. When I say "larid", I am referring to any bird in the suborder Lari except for the alcids. Or, in normal English, any gull, tern, skimmer, skua, or jaeger.

Albatrosses actually aren't larids by anyone's definition. They're a type of tubenose, belonging to the order Procellariiformes. These birds all have specialized nostrils with a salt removal gland that lets them drink seawater without ill effect (other than secreting an incredibly concentrated salt solution from their noses). The main visible difference between tubenoses and larids is that tubenoses almost never flap their wings (except for the storm-petrels, which are too small to be confused with any gull).

All in all, you really don't have to worry about confusing tubenoses and larids while near the shore: it is highly unlikely that you will see a tubenose. They spend nearly their entire lives at sea and only come on land to nest and lay eggs. They're usually at least a mile from shore, though sometimes after storms they are blown inland and show up in ridiculous places (like the Salton Sea in southern California).

And now, selected videos of various coastal birds (I don't have a good video camera, so I'll refer you to YouTube):

Grebe courtship (the best part is at the end)

Bufflehead (a diving duck)

No video can do tern flight justice, but this is pretty good.

Slow-mo Jaeger (once again, you really have to see this kind of thing in real life)

Hanging out and looking cool

A couple of storm-petrels. Hatteras is pretty much the one place where you have a chance of seeing them.

Awwwww...

Wait, this might be even cuter. The babies show up about halfway through.

Enjoy!

Friday, December 14, 2012

Thursday, December 13, 2012

It's Not Over 'til the Fat Hen Sings...

...and since in the majority of bird species it is the male that sings, it isn't over!

This is in no way a "last post". Nonfiction Writing is coming to an end, but The Flyway Truck Stop will still be here for your perusal. Sighting updates will continue, pictures will be posted, and more bird stories will be told. I also plan on opening the blog up to the entire Uni community, not just the Nonfiction Writing classes. Which brings me to the topic of What Is It?

It really wouldn't be fair to people not in Nonfiction Writing if those of you who had participated in What Is It? before had a head start (especially a 30-point head start) on the scoreboard. So for 2013, the scoreboard will be reset to zero. But don't worry. You still have a chance for glory before the scope of the competition increases.

There will be one last What Is It? this year, and it's a bit different from those that have come before it. I was considering doing something easy after the Coastal Challenge flopped, but then I thought, why would I ever do that? So here's a briefing of the upcoming What Is It? 2012 Championship Final Round.

First of all, there is a limited time span in which to identify the birds. Submissions are open from Saturday, December 15th to Saturday, December 22nd. As in, finals week, or a little bit later or earlier.

Rather than score based on who answers first, the challenge will be set up a bit like "Who Wants to be a Millionaire" with progressively harder and harder questions (which might not necessarily be images) with progressively increasing point values. You get points starting with question #1 up until you have an incorrect answer. Go ahead and post all of your answers in one comment if you want to. Correct answers on all 10 questions will get you a total of 55 points!

So keep an eye out for the What Is It? 2012 Championship Final Round and come back after winter break for the opening round of What Is It? 2013.

Happy birding!

This is in no way a "last post". Nonfiction Writing is coming to an end, but The Flyway Truck Stop will still be here for your perusal. Sighting updates will continue, pictures will be posted, and more bird stories will be told. I also plan on opening the blog up to the entire Uni community, not just the Nonfiction Writing classes. Which brings me to the topic of What Is It?

It really wouldn't be fair to people not in Nonfiction Writing if those of you who had participated in What Is It? before had a head start (especially a 30-point head start) on the scoreboard. So for 2013, the scoreboard will be reset to zero. But don't worry. You still have a chance for glory before the scope of the competition increases.

There will be one last What Is It? this year, and it's a bit different from those that have come before it. I was considering doing something easy after the Coastal Challenge flopped, but then I thought, why would I ever do that? So here's a briefing of the upcoming What Is It? 2012 Championship Final Round.

First of all, there is a limited time span in which to identify the birds. Submissions are open from Saturday, December 15th to Saturday, December 22nd. As in, finals week, or a little bit later or earlier.

Rather than score based on who answers first, the challenge will be set up a bit like "Who Wants to be a Millionaire" with progressively harder and harder questions (which might not necessarily be images) with progressively increasing point values. You get points starting with question #1 up until you have an incorrect answer. Go ahead and post all of your answers in one comment if you want to. Correct answers on all 10 questions will get you a total of 55 points!

So keep an eye out for the What Is It? 2012 Championship Final Round and come back after winter break for the opening round of What Is It? 2013.

Happy birding!

Tuesday, December 11, 2012

Coastal Challenge Walkthrough

Okay, maybe the Coastal Challenge was a bit difficult.

Or really difficult.

In fact, there was only one correct answer submitted: Gloria was right about the Black Turnstones in the first picture. Daniel had the right species but the wrong picture; the Common Loon is the center bird in picture #2.

Well, teachable moment time! Here's a walkthrough of how to do all the ID's:

There are 6 main groups of birds you should consider when looking at birds near or on the water:

Loons and grebes:

Loons have long bodies with short necks and sit low in the water. They tend to be larger than other swimming birds. They dive less frequently than other birds, but stay under for a long time. All have thick, dagger-shaped beaks.

Grebes have short bodies but long necks and sit low in the water. They tend to be on the small side. They dive almost constantly. In most species, the beak is long and slender.

Waterfowl (ducks, geese, swans, etc):

Diving ducks tend to be smaller than Mallards, and have relatively short necks. Their beaks are wedge-shaped, except for the long, serrated beaks of mergansers.

Cormorants:

Cormorants all have long bodies and long necks, with skinny beaks that appear squarish or hooked.

Shorebirds (plover, sandpipers, etc):

Plover have short necks and short beaks mounted on relatively plump bodies and long legs.

Large sandpipers tend to have longer necks, longer beaks, and even longer legs than plover. Smaller sandpipers have almost no neck and tiny heads.

Oddities such as oystercatchers and avocets are instantly recognizable by their odd beak shapes.

Larids (gulls, terns, etc):

All species have very long wings and are more likely to be flying than swimming. Gulls spend a lot of time gliding, while terns flap almost constantly. Terns also have proportionately longer, pointier wings and beaks. Most tern species are white with a black cap on the head and a colorful beak.

Alcids (puffins, auks, etc):

These are plump, short-tailed swimming birds that can't fly very well. Like grebes, they dive almost constantly, though they have very short necks. They are only found on the ocean.

Picture #1: The first thing to notice is that these birds are standing, not swimming, which actually means a lot in a coastal setting. Grebes, loons, auks, and diving ducks are just plain clumsy on land, and avoid it whenever they can. Cormorants will perch sometimes, but the body proportions on these guys are definitely not those of cormorants (necks are too short). These are certainly not gulls (no North American gull has a brown back and head), so we're left with shorebirds. The main feature of these birds are the dark grey-brown backs, chests, and heads, with a rather elaborate pattern on them if you look closely. They're too dark to be plover or "peeps" (genus Calidris). The beaks are too small for these birds to be juvenile American Oystercatchers, so we're pretty much left with sandpipers. The body proportions (awfully chunky and short-necked and short-billed) leave us with four main suspects: Ruddy Turnstone, Black Turnstone, Surfbird, or Rock Sandpiper. Out of these, only the Black Turnstone and Surfbird are dark enough overall, but the Surfbird lacks the all-dark beak. Thus these three castaways are Black Turnstones (Arenaria melanocephala)

Picture #2: We'll start with the bird in the middle.The first thing to notice is that it's swimming with a really low profile, which eliminates shorebirds, larids, geese, and swans. And it's noticeably larger than the other birds in the picture. Except for eiders (which don't normally occur in Oregon), sea ducks tend to be fairly small, so we're left with alcids, loons, grebes, or cormorants. The neck is too short for a cormorant or grebe, and alcids tend to be on the small side. The bird's dagger-shaped bill confirms that it's a loon. Loon species, unfortunately, are difficult to differentiate, and all of the North American species of loon can potentially show up in Oregon. Additionally, this bird is either a juvenile or a bird not yet in breeding plumage. So we go by process of elimination. The Red-throated and Pacific loons are small, with longer, thinner necks and beaks. Yellow-billed Loons have yellow bills (duh) and hold their heads at a rather steep upward angle. Arctic Loons have relatively small heads. Thus this bird is a Common Loon (Gavia immer).

The bird on the far right has a crazy-looking white-and-orange pattern on its face. The beak is shaped like a triangle and is pretty much flat along the bottom, an indicator that this bird is a sea duck. Identifying this one is mostly a matter of browsing the duck section until you stumble across the male Surf Scoter (Melanitta perspicillata) with his just plain weird facial plumage. Here's a closer (and landlubbing) image of one, taken in San Diego, CA:

#3: This is the same bird as the one on the left in picture #2. Once again, it's swimming, so we're considering loons, grebes, ducks, geese, cormorants, and alcids. Note that this bird has an incredibly short body and tail plus a HUGE head with a really long, narrow, slightly curved beak. No waterfowl, loon, or cormorant has a beak like that (cormorants and loons also have long bodies). Grebes tend to have long necks, so we're left with alcids.

Very few people have heard of any alcids other than puffins, and they're not all nicely arranged near the front of the book, so I'll bet that most of you who tried the challenge probably never even checked the alcid section. Well, they're good birds to know, mostly because my favorite species (Aethia cristatella) is one of them. Alcids have short, fat bodies (check), short tails (check), and swim on the open ocean (check). Most have a black on top/white on bottom color scheme, except for the guillemots, auklets, and Tufted Puffins. Just by looking at this bird's long, skinny beak we can eliminate puffins and auklets. Now we just have to differentiate between the two guillemot species (clarification: I'm using the American definition of guillemot; in Britain, it can apply to the genera Cepphus or Uria). The Black Guillemot does not normally occur in Oregon, but don't count it completely out of consideration (identifying birds based on range is baaad). Instead, note the little black triangle at the bottom of the white patch on the wing. It's not as extreme as it is depicted in many illustrations, but it's the field mark nonetheless. This bird is a Pigeon Guillemot (Cepphus columba).

#4: We're starting with the bird in the center again. Look at that back and neck profile: low in the water, with a Loch Ness monster curve leading up to the head. We can instantly declare this to be either a grebe or cormorant. The beak is oddly square-shaped, and held at an upward angle, neither of which are a characteristic of grebes. This bird is a cormorant.

Oh, boy.

I'm not going to lie. Cormorant species are really hard to tell apart, since they're all big black birds that spend their time in the water. Luckily, this bird has ONE HUGE FIELD MARK that allows us to figure out what it is: look at that white spot on its rear. Only two cormorant species have this: Pelagic and Red-faced. Our bird's head is too small and slender for this to be a Red-faced, so it's a Pelagic Cormorant (Phalacrocorax pelagicus).

The two birds near the bottom right, on the other hand, have their bodies pretty high up in the water and are really rather colorful; this restricts our search to waterfowl. Notice the crazy tufts on their heads, and the thin, coral-colored beak on the nearest one. These field marks indicate that we have found mergansers. With only four possible North American species, this ID is rather simple: the crazy white-and-black patterns on the male plus the rather drab plumage of the female tell us that these are Red-breasted Mergansers (Mergus serrator). Unfortunately, this is the best picture I have of either species.

#5: This one is in some ways the most difficult, but in other ways rather easy. And it's my favorite.

There's very little to see in this photograph (don't blame me, the bird was a quarter mile away), but it's enough. Low profile, long neck: it's a grebe or cormorant. Huge white patch on face plus super-skinny yellowish beak: not a cormorant. There are 7 North American species of grebe, with varying lengths of necks and beaks. Let's do process of elimination again:

Horned Grebe: our bird's beak is too long.

Eared Grebe: our bird has too much white on the face.

Pied-billed Grebe: our bird's beak is way too long and skinny, and it's plumage has too many different colors for it to be a pied-billed.

Least Grebe: body proportions are all wrong. And it would freeze to death in Oregon.

Clark's Grebe: our bird's neck is too short, and it's completely dark.

Western Grebe: same as Clark's Grebe.

The huge white triangle on the bird's face, with black on the forehead and a brownish neck, confirms our answer: this is a Red-necked Grebe (Podiceps grisegena), which I regard as quite possibly the most beautiful bird in the world. Macaws? Birds of Paradise? Tanagers? Get real. This bird wins with its sheer elegance and the richness of it's limited color palette. Unfortunately, I never got one to come close enough to get a good picture. So search the internet instead.

As for the bird in the dark in Texas, Daniel was on the right track... sort of. This bird shares a lot in common with chickadees, namely the large head and grey/black/white overall coloration. But there are a couple of things that it doesn't share with chickadees, only a few of which can be noticed in the picture: It only has a black mask on its face, not a full black cap (you can see a bit of light grey over the eyes in the second picture). Chickadees like forests. There aren't many trees on the outskirts of San Antonio. This is a bird of dry, brushy areas.

What you can't tell from the picture is that this cute, cardinal-sized puffball has a penchant for catching small animals and snapping their necks before impaling them on thorns so they dry up like beef jerky and can be eaten later. A bit of an oddity in the world, this is a predatory songbird. And I'm not talking about bugs; lots of songbirds eat bugs. No, the menu for this species' lunch occasionally includes frogs, lizards, snakes, mice, and even other birds. I present to you: the Loggerhead Shrike! (Lanius ludovicianus)

The really odd thing, though, is that even though it seemed like there was one of these on every telephone wire in the area (there was one day I counted more of them than any other species besides Rock Dove and House Sparrow) I never actually got a good picture of one. Oh, well. Someday.

But remember, you still got points for trying! And keep an eye out for What Is It? Round 8, which will be easier.

Or really difficult.

In fact, there was only one correct answer submitted: Gloria was right about the Black Turnstones in the first picture. Daniel had the right species but the wrong picture; the Common Loon is the center bird in picture #2.

Well, teachable moment time! Here's a walkthrough of how to do all the ID's:

There are 6 main groups of birds you should consider when looking at birds near or on the water:

Loons and grebes:

Loons have long bodies with short necks and sit low in the water. They tend to be larger than other swimming birds. They dive less frequently than other birds, but stay under for a long time. All have thick, dagger-shaped beaks.

Grebes have short bodies but long necks and sit low in the water. They tend to be on the small side. They dive almost constantly. In most species, the beak is long and slender.

Waterfowl (ducks, geese, swans, etc):

Diving ducks tend to be smaller than Mallards, and have relatively short necks. Their beaks are wedge-shaped, except for the long, serrated beaks of mergansers.

Cormorants:

Cormorants all have long bodies and long necks, with skinny beaks that appear squarish or hooked.

Shorebirds (plover, sandpipers, etc):

Plover have short necks and short beaks mounted on relatively plump bodies and long legs.

Large sandpipers tend to have longer necks, longer beaks, and even longer legs than plover. Smaller sandpipers have almost no neck and tiny heads.

Oddities such as oystercatchers and avocets are instantly recognizable by their odd beak shapes.

Larids (gulls, terns, etc):

All species have very long wings and are more likely to be flying than swimming. Gulls spend a lot of time gliding, while terns flap almost constantly. Terns also have proportionately longer, pointier wings and beaks. Most tern species are white with a black cap on the head and a colorful beak.

Alcids (puffins, auks, etc):

These are plump, short-tailed swimming birds that can't fly very well. Like grebes, they dive almost constantly, though they have very short necks. They are only found on the ocean.

Picture #1: The first thing to notice is that these birds are standing, not swimming, which actually means a lot in a coastal setting. Grebes, loons, auks, and diving ducks are just plain clumsy on land, and avoid it whenever they can. Cormorants will perch sometimes, but the body proportions on these guys are definitely not those of cormorants (necks are too short). These are certainly not gulls (no North American gull has a brown back and head), so we're left with shorebirds. The main feature of these birds are the dark grey-brown backs, chests, and heads, with a rather elaborate pattern on them if you look closely. They're too dark to be plover or "peeps" (genus Calidris). The beaks are too small for these birds to be juvenile American Oystercatchers, so we're pretty much left with sandpipers. The body proportions (awfully chunky and short-necked and short-billed) leave us with four main suspects: Ruddy Turnstone, Black Turnstone, Surfbird, or Rock Sandpiper. Out of these, only the Black Turnstone and Surfbird are dark enough overall, but the Surfbird lacks the all-dark beak. Thus these three castaways are Black Turnstones (Arenaria melanocephala)

|

| Photo by the author. |

Picture #2: We'll start with the bird in the middle.The first thing to notice is that it's swimming with a really low profile, which eliminates shorebirds, larids, geese, and swans. And it's noticeably larger than the other birds in the picture. Except for eiders (which don't normally occur in Oregon), sea ducks tend to be fairly small, so we're left with alcids, loons, grebes, or cormorants. The neck is too short for a cormorant or grebe, and alcids tend to be on the small side. The bird's dagger-shaped bill confirms that it's a loon. Loon species, unfortunately, are difficult to differentiate, and all of the North American species of loon can potentially show up in Oregon. Additionally, this bird is either a juvenile or a bird not yet in breeding plumage. So we go by process of elimination. The Red-throated and Pacific loons are small, with longer, thinner necks and beaks. Yellow-billed Loons have yellow bills (duh) and hold their heads at a rather steep upward angle. Arctic Loons have relatively small heads. Thus this bird is a Common Loon (Gavia immer).

|

| Photo by the author. |

The bird on the far right has a crazy-looking white-and-orange pattern on its face. The beak is shaped like a triangle and is pretty much flat along the bottom, an indicator that this bird is a sea duck. Identifying this one is mostly a matter of browsing the duck section until you stumble across the male Surf Scoter (Melanitta perspicillata) with his just plain weird facial plumage. Here's a closer (and landlubbing) image of one, taken in San Diego, CA:

|

| Photo by the author. |

Very few people have heard of any alcids other than puffins, and they're not all nicely arranged near the front of the book, so I'll bet that most of you who tried the challenge probably never even checked the alcid section. Well, they're good birds to know, mostly because my favorite species (Aethia cristatella) is one of them. Alcids have short, fat bodies (check), short tails (check), and swim on the open ocean (check). Most have a black on top/white on bottom color scheme, except for the guillemots, auklets, and Tufted Puffins. Just by looking at this bird's long, skinny beak we can eliminate puffins and auklets. Now we just have to differentiate between the two guillemot species (clarification: I'm using the American definition of guillemot; in Britain, it can apply to the genera Cepphus or Uria). The Black Guillemot does not normally occur in Oregon, but don't count it completely out of consideration (identifying birds based on range is baaad). Instead, note the little black triangle at the bottom of the white patch on the wing. It's not as extreme as it is depicted in many illustrations, but it's the field mark nonetheless. This bird is a Pigeon Guillemot (Cepphus columba).

|

| Photo by the author. That's about as close as he ever came. |

#4: We're starting with the bird in the center again. Look at that back and neck profile: low in the water, with a Loch Ness monster curve leading up to the head. We can instantly declare this to be either a grebe or cormorant. The beak is oddly square-shaped, and held at an upward angle, neither of which are a characteristic of grebes. This bird is a cormorant.

Oh, boy.

I'm not going to lie. Cormorant species are really hard to tell apart, since they're all big black birds that spend their time in the water. Luckily, this bird has ONE HUGE FIELD MARK that allows us to figure out what it is: look at that white spot on its rear. Only two cormorant species have this: Pelagic and Red-faced. Our bird's head is too small and slender for this to be a Red-faced, so it's a Pelagic Cormorant (Phalacrocorax pelagicus).

The two birds near the bottom right, on the other hand, have their bodies pretty high up in the water and are really rather colorful; this restricts our search to waterfowl. Notice the crazy tufts on their heads, and the thin, coral-colored beak on the nearest one. These field marks indicate that we have found mergansers. With only four possible North American species, this ID is rather simple: the crazy white-and-black patterns on the male plus the rather drab plumage of the female tell us that these are Red-breasted Mergansers (Mergus serrator). Unfortunately, this is the best picture I have of either species.

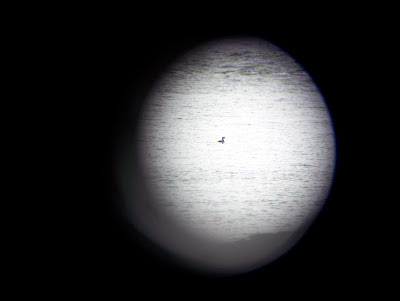

#5: This one is in some ways the most difficult, but in other ways rather easy. And it's my favorite.

There's very little to see in this photograph (don't blame me, the bird was a quarter mile away), but it's enough. Low profile, long neck: it's a grebe or cormorant. Huge white patch on face plus super-skinny yellowish beak: not a cormorant. There are 7 North American species of grebe, with varying lengths of necks and beaks. Let's do process of elimination again:

Horned Grebe: our bird's beak is too long.

Eared Grebe: our bird has too much white on the face.

Pied-billed Grebe: our bird's beak is way too long and skinny, and it's plumage has too many different colors for it to be a pied-billed.

Least Grebe: body proportions are all wrong. And it would freeze to death in Oregon.

Clark's Grebe: our bird's neck is too short, and it's completely dark.

Western Grebe: same as Clark's Grebe.

The huge white triangle on the bird's face, with black on the forehead and a brownish neck, confirms our answer: this is a Red-necked Grebe (Podiceps grisegena), which I regard as quite possibly the most beautiful bird in the world. Macaws? Birds of Paradise? Tanagers? Get real. This bird wins with its sheer elegance and the richness of it's limited color palette. Unfortunately, I never got one to come close enough to get a good picture. So search the internet instead.

As for the bird in the dark in Texas, Daniel was on the right track... sort of. This bird shares a lot in common with chickadees, namely the large head and grey/black/white overall coloration. But there are a couple of things that it doesn't share with chickadees, only a few of which can be noticed in the picture: It only has a black mask on its face, not a full black cap (you can see a bit of light grey over the eyes in the second picture). Chickadees like forests. There aren't many trees on the outskirts of San Antonio. This is a bird of dry, brushy areas.

What you can't tell from the picture is that this cute, cardinal-sized puffball has a penchant for catching small animals and snapping their necks before impaling them on thorns so they dry up like beef jerky and can be eaten later. A bit of an oddity in the world, this is a predatory songbird. And I'm not talking about bugs; lots of songbirds eat bugs. No, the menu for this species' lunch occasionally includes frogs, lizards, snakes, mice, and even other birds. I present to you: the Loggerhead Shrike! (Lanius ludovicianus)

The really odd thing, though, is that even though it seemed like there was one of these on every telephone wire in the area (there was one day I counted more of them than any other species besides Rock Dove and House Sparrow) I never actually got a good picture of one. Oh, well. Someday.

But remember, you still got points for trying! And keep an eye out for What Is It? Round 8, which will be easier.

Monday, December 3, 2012

The Big December Backyard Watch!

Winter is almost here, which means everything is going to start getting cold, dreary, and otherwise uninhabitable. Many birds have already headed south on their migration, but...

There are still plenty around! There are a number of species that hang around here in Champaign-Urbana during the colder months of the year, and since food is a bit scarce elsewhere they are more likely to come visit birdfeeders in your backyard.

So here's the challenge (well, hopefully it isn't challenging): During the month of December, see how many species of birds visit your backyard. Or your relatives' backyards. Or visible from your backyard even though it's just flying over. Well, it doesn't even have to be a backyard. Basically, we're going for a list of every single bird species seen by a Nonfiction Writing student this month.

I've set up a checklist on the side of the blog with the most common backyard birds; results may vary depending on what kind of habitat can be found in your backyard, etc, etc. When you see one of those species, vote for it in the poll. If you see something that isn't on the list, reply with a comment to this post saying what you saw.

Ready? Happy birding!

If you want advice regarding birdfeeders and such, check out the post Be Patient... Or Not from October 17th. Also, The Coastal Challenge is still accepting answers, as is the mystery bird in the dark from What Is It? Round 6.

There are still plenty around! There are a number of species that hang around here in Champaign-Urbana during the colder months of the year, and since food is a bit scarce elsewhere they are more likely to come visit birdfeeders in your backyard.

So here's the challenge (well, hopefully it isn't challenging): During the month of December, see how many species of birds visit your backyard. Or your relatives' backyards. Or visible from your backyard even though it's just flying over. Well, it doesn't even have to be a backyard. Basically, we're going for a list of every single bird species seen by a Nonfiction Writing student this month.

I've set up a checklist on the side of the blog with the most common backyard birds; results may vary depending on what kind of habitat can be found in your backyard, etc, etc. When you see one of those species, vote for it in the poll. If you see something that isn't on the list, reply with a comment to this post saying what you saw.

Ready? Happy birding!

If you want advice regarding birdfeeders and such, check out the post Be Patient... Or Not from October 17th. Also, The Coastal Challenge is still accepting answers, as is the mystery bird in the dark from What Is It? Round 6.

Sunday, November 25, 2012

Awwwww...

|

| Photo by the author. No zoom. |

Happy Thanksgiving!

(And remember to try the Coastal Challenge)

Tuesday, November 20, 2012

Colbert Park: Champaign County's Worst Best Place to go Birding

(Remember, the Coastal Challenge is still open for answers!)

Colbert Park in Savoy first came to my attention when one of my fellow birders brought in a picture of some ducks he had seen there while fishing. He was asking some of the more experienced members of the Audubon Society for help identifying them. Both of the ducks belonged to the genus Aythya, a group of diving ducks. One was a Redhead (Aythya americana) and the other was a Greater Scaup (Aythya marila). Neither was a species I would ever have expected to find in a Savoy subdivision.

It took me until earlier this fall to actually go out to this mystical duck pond to see what I could find; the results were rather disappointing. The only birds I found were a couple of Kildeer. I blamed the emptiness on the weather, since it was cloudy and nearly raining. I did notice, however, that from a birding perspective the park is really rather unimpressive. There is literally no habitat at Colbert Park--there's a few scrawny saplings, but otherwise the only vegetation is short grass. The weedy, undeveloped field to the west of the park looked like a much better place to look for birds. The only thing Colbert Park has going for it is the big, deep lake.

Two Saturdays ago, I headed out on my bike to go down to Curpros Pond and see what I could find. When I got there, I was dismayed to find that the field next to it was being plowed, and I figured the dust and noise would keep most birds away. I instead ventured into the nearby subdivision to check out another pond that had been recommended to me by fellow birder Rob Kanter. There, I found the usual mass of Canada Geese and Mallards, but there were three pleasant surprises: a Double-Crested Cormorant made a brief flyover, and mixed in with the Mallards were a couple of American Widgeons and an American Black Duck.

Once I felt I had seen everything there was to see, I proceeded to get myself lost in the subdivision. When I finally escaped, I found myself on Dunlap Avenue (which is apparently what they call Neil Street in Savoy) less than half a mile north of Colbert Park.

When I rode down to the water, I happily noticed that there were a lot more birds on the lake than there had been the previous time. True, they were all Canada Geese, but there were at least two hundred of them. I made my way slowly along the shore towards the fishing pier, every once in a while stopping to check the water for anything other than Branta canadensis. I found a small flotilla of diving ducks out in the middle of the water, but they were too backlit to be identified from where I was standing.

I finally made it to the fishing pier, from where I could survey the lake with the sun conveniently behind me. I got a much better look at my duck friends, which turned out to be a half-dozen or so Ring-Necked Ducks and a lone Bufflehead. I also found an American Coot and what I'm fairly certain was a Pied-Billed Grebe near the far shore. A flock of thirty or so Kildeer flew by. Less than twenty feet away from where I was standing were nine or ten Cackling Geese mixed in with the Canadas--easily the best look I've ever gotten at that species. And they're so CUTE!!! To top everything off, around four-and-twenty Brewer's Blackbirds came down to the far shore to drink before moving back into the weedy field.

At this point, I was sure that Colbert Park was a great place to go birding. After all, I had just seen three species (Ring-Necked Duck, Bufflehead, and Brewer's Blackbird) that I'd never found in Champaign County before, plus a close-up of a bunch of Cackling Geese. I was sure I had finally found the great waterfowl-watching wonderland I had always wanted to have somewhere nearby.

Unfortunately, Colbert Park is about as reliable as a Yugo. I've gone there two times since then, and in both instances I have seen no birds there. As in, NO BIRDS OF ANY SPECIES WHATSOEVER. Not even Rock Doves, House Sparrows, or European Starlings. It seems that no matter what the weather is, the utter lack of anything but water at Colbert Park means that nothing is going to hang around there for very long (not to mention the fact that it's a popular place for people to walk their dogs). Birding there is all about being in the right place at the right time; if you don't get lucky and show up when a migratory flock just happens to have stopped by, you won't see diddly-squat.

In any case I'll have to say that I don't recommend going to Colbert Park for birding unless you live nearby or bring your fishing equipment so you have something to do when it turns out there's nothing to see. It has the potential to be a great birding spot; you just have to win the lottery when it comes to when that potential is being used. If you want a good, solid waterfowl viewing area, it would seem that Mahomet's Riverbend Forest Preserve is the best option.

(Note: Riverbend also has a matter of timing involved, but at least it's reliable on a daily basis. In winter, the best time to be there is in the 3:30-5:30PM range.)

(Unless the whole thing is frozen over, in which case don't bother.)

Happy Birding!

Colbert Park in Savoy first came to my attention when one of my fellow birders brought in a picture of some ducks he had seen there while fishing. He was asking some of the more experienced members of the Audubon Society for help identifying them. Both of the ducks belonged to the genus Aythya, a group of diving ducks. One was a Redhead (Aythya americana) and the other was a Greater Scaup (Aythya marila). Neither was a species I would ever have expected to find in a Savoy subdivision.

It took me until earlier this fall to actually go out to this mystical duck pond to see what I could find; the results were rather disappointing. The only birds I found were a couple of Kildeer. I blamed the emptiness on the weather, since it was cloudy and nearly raining. I did notice, however, that from a birding perspective the park is really rather unimpressive. There is literally no habitat at Colbert Park--there's a few scrawny saplings, but otherwise the only vegetation is short grass. The weedy, undeveloped field to the west of the park looked like a much better place to look for birds. The only thing Colbert Park has going for it is the big, deep lake.

Two Saturdays ago, I headed out on my bike to go down to Curpros Pond and see what I could find. When I got there, I was dismayed to find that the field next to it was being plowed, and I figured the dust and noise would keep most birds away. I instead ventured into the nearby subdivision to check out another pond that had been recommended to me by fellow birder Rob Kanter. There, I found the usual mass of Canada Geese and Mallards, but there were three pleasant surprises: a Double-Crested Cormorant made a brief flyover, and mixed in with the Mallards were a couple of American Widgeons and an American Black Duck.

|

| Photo by the author. View full size so you can see labels. |

When I rode down to the water, I happily noticed that there were a lot more birds on the lake than there had been the previous time. True, they were all Canada Geese, but there were at least two hundred of them. I made my way slowly along the shore towards the fishing pier, every once in a while stopping to check the water for anything other than Branta canadensis. I found a small flotilla of diving ducks out in the middle of the water, but they were too backlit to be identified from where I was standing.

I finally made it to the fishing pier, from where I could survey the lake with the sun conveniently behind me. I got a much better look at my duck friends, which turned out to be a half-dozen or so Ring-Necked Ducks and a lone Bufflehead. I also found an American Coot and what I'm fairly certain was a Pied-Billed Grebe near the far shore. A flock of thirty or so Kildeer flew by. Less than twenty feet away from where I was standing were nine or ten Cackling Geese mixed in with the Canadas--easily the best look I've ever gotten at that species. And they're so CUTE!!! To top everything off, around four-and-twenty Brewer's Blackbirds came down to the far shore to drink before moving back into the weedy field.

|

| Photo by the author. Notice how small the Cackling Geese are compared to their ubiquitous look-alikes. |

|

| Photo by the author. Nine Cackling, five Canada. |

|

| Photo by the author. Six Canada Geese and four Ring-Necked Ducks. Can you also find all eight Kildeer? (You'll have to zoom in a lot) |

|

| Photo by the author. Canada Geese in the water and Brewer's Blackbirds on the shore. Also one Ring-Necked Duck and one Kildeer. |

At this point, I was sure that Colbert Park was a great place to go birding. After all, I had just seen three species (Ring-Necked Duck, Bufflehead, and Brewer's Blackbird) that I'd never found in Champaign County before, plus a close-up of a bunch of Cackling Geese. I was sure I had finally found the great waterfowl-watching wonderland I had always wanted to have somewhere nearby.

Unfortunately, Colbert Park is about as reliable as a Yugo. I've gone there two times since then, and in both instances I have seen no birds there. As in, NO BIRDS OF ANY SPECIES WHATSOEVER. Not even Rock Doves, House Sparrows, or European Starlings. It seems that no matter what the weather is, the utter lack of anything but water at Colbert Park means that nothing is going to hang around there for very long (not to mention the fact that it's a popular place for people to walk their dogs). Birding there is all about being in the right place at the right time; if you don't get lucky and show up when a migratory flock just happens to have stopped by, you won't see diddly-squat.

In any case I'll have to say that I don't recommend going to Colbert Park for birding unless you live nearby or bring your fishing equipment so you have something to do when it turns out there's nothing to see. It has the potential to be a great birding spot; you just have to win the lottery when it comes to when that potential is being used. If you want a good, solid waterfowl viewing area, it would seem that Mahomet's Riverbend Forest Preserve is the best option.

(Note: Riverbend also has a matter of timing involved, but at least it's reliable on a daily basis. In winter, the best time to be there is in the 3:30-5:30PM range.)

(Unless the whole thing is frozen over, in which case don't bother.)

Happy Birding!

Monday, November 12, 2012

The Coastal Challenge! (aka What Is It? Round 7)

For those of you who tried last week's What Is It? challenge, go to the Lazuli Bunting page on Cornell University's All About Birds site and scroll down to the bottom so you can see the "similar species."

Yup. That was a Blue Grosbeak (Passerina caerulea). Congrats to Julia for her correct ID.

No one got the bird in the dark correct (it is not a verdin, great kiskadee, or black-capped chickadee), so I've decided to give everyone a second week to answer that one. Here are a few hints regarding that particular bird:

1. It is comparable to a northern cardinal in size

2. The area it is in has a few trees, but most of the habitat is scrub

Answers for the bird in the dark are due on November 19th.

Now get out those field guides and raincoats, because we're heading out to dreary shores of Garibaldi, Oregon for a waterbird extravaganza! It's time for...

But first, some general info on birding by the sea.

Coastal areas are perhaps the best places for birding, especially in lagoons, tidal marshes, bays, and jetties. You can find hundreds of species in the same place: ducks, geese, grebes, loons, herons, sandpipers, plover, cormorants, pelicans, rails, falcons, eagles, gulls, terns, skuas, murres, auks, puffins, pipits, sparrows, blackbirds--the list goes on and on. Best of all, they tend to be out in the open and fairly easy to see (there's not much to hide them on the open water or along the shore).

One of the best things for beginners about birds along the coast is that their daily schedule is not governed by the sun. For warblers and other migratory forest birds, you pretty much have to go birding really early in the morning to see them. Seabirds and shorebirds, however, go by the tides. You can go to a tidal marsh or jetty at high tide and it will be filled with diving ducks and grebes; if you visit the same location at low tide, the ducks will be gone and replaced with sandpipers and plover. If you are on vacation to the coast, consider visiting a beach near a wildlife refuge. Pay attention to the birds that fly by--not everything is a gull! In southern California you can find lots of terns, cormorants, pelicans, and sometimes even skimmers at popular state beaches.

There are two problems with birding near the ocean:

1. We don't have any around here.

2. Waterbirds can be tough because of how far away they are from shore.

On that note, you'll have to use all of your birding ability to get these ID's. When you post your answers, identify which picture they go with. Remember, in order to get full points you must identify the species, not just family or genus. Ready? Have fun!

#1: Perched on a shipwreck near a clam processing plant...

#2: A trio out on the bay...

#3: The leftmost bird in the previous photo is tough... here's another view of it.

#4: More swimmers!

#5: This one was so far away it could only be photographed through a spotting scope...

Answers for the Coastal Challenge are due by Monday, December 10th.

(Yeah, I extended it again. Again.)

Happy identification!

Yup. That was a Blue Grosbeak (Passerina caerulea). Congrats to Julia for her correct ID.

No one got the bird in the dark correct (it is not a verdin, great kiskadee, or black-capped chickadee), so I've decided to give everyone a second week to answer that one. Here are a few hints regarding that particular bird:

1. It is comparable to a northern cardinal in size

2. The area it is in has a few trees, but most of the habitat is scrub

Answers for the bird in the dark are due on November 19th.

Now get out those field guides and raincoats, because we're heading out to dreary shores of Garibaldi, Oregon for a waterbird extravaganza! It's time for...

The Coastal Challenge

That's right... 5 photos, 7 species, and only 3 weeks to identify them all!But first, some general info on birding by the sea.

Coastal areas are perhaps the best places for birding, especially in lagoons, tidal marshes, bays, and jetties. You can find hundreds of species in the same place: ducks, geese, grebes, loons, herons, sandpipers, plover, cormorants, pelicans, rails, falcons, eagles, gulls, terns, skuas, murres, auks, puffins, pipits, sparrows, blackbirds--the list goes on and on. Best of all, they tend to be out in the open and fairly easy to see (there's not much to hide them on the open water or along the shore).

One of the best things for beginners about birds along the coast is that their daily schedule is not governed by the sun. For warblers and other migratory forest birds, you pretty much have to go birding really early in the morning to see them. Seabirds and shorebirds, however, go by the tides. You can go to a tidal marsh or jetty at high tide and it will be filled with diving ducks and grebes; if you visit the same location at low tide, the ducks will be gone and replaced with sandpipers and plover. If you are on vacation to the coast, consider visiting a beach near a wildlife refuge. Pay attention to the birds that fly by--not everything is a gull! In southern California you can find lots of terns, cormorants, pelicans, and sometimes even skimmers at popular state beaches.

There are two problems with birding near the ocean:

1. We don't have any around here.

2. Waterbirds can be tough because of how far away they are from shore.

On that note, you'll have to use all of your birding ability to get these ID's. When you post your answers, identify which picture they go with. Remember, in order to get full points you must identify the species, not just family or genus. Ready? Have fun!

#1: Perched on a shipwreck near a clam processing plant...

|

| Photo by the author. |

|

| Photo by the author. |

|

| Photo by the author. |

|

| Photo by the author. |

|

| Photo by the author. |

Answers for the Coastal Challenge are due by Monday, December 10th.

(Yeah, I extended it again. Again.)

Happy identification!

Thursday, November 1, 2012

Owls and You (and discussion of poo!)

(For those of you who are hypercompetitive, What Is It? (Round 6) is below this post)

The results of the poll that I had up on the side of the blog last month indicate that readers like owls. So I'll write a post about watching owls.

To tell the truth, your best chance of finding owls is to go to the Anita Purves Nature Center and go see the Eastern Screech Owls they have inside. As for wild owls, things are a bit trickier.

The main problem with watching owls, of course, is that they are primarily nocturnal. It's very unlikely that you'll be able to see them when they're most active (I've actually seen two owls in the middle of the night: one flew under a streetlight and the other I identified based on its reflection on a moonlit pond as it flew overhead).

Don't despair, though! It is possible to see owls during the day.

But it's really hard.

HOW TO LOOK FOR OWLS:

One option is to try to find owls that are sleeping. Here are tricks for that:

1. Look in holes. Owls like to sleep in tree cavities or large birdhouses. Unfortunately, if the hole is big enough (like they prefer) they will not be visible from outside.

2. Check for "whitewash". Small owls often perch in the same tree many times. And while sitting there, they have to... well... do their business.

Time to learn about poop!

Unlike mammals, birds do not have separate liquid and solid waste. Instead, it all gets mixed up in the last stage of the bird's digestive tract. Solid waste is the little black or grey lumps. The white stuff that makes the wonderful little splats on the windshield of your car is the urine. Human urine packages the waste into the chemical urea, which is easy to synthesize but requires a lot of water to flush out of the excretory system. That's why human urine is clear. Birds, on the other hand, use the more complex chemical uric acid. Uric acid requires very little water to carry it out of the bird, so their urine is opaque and viscous.

Anyway, owls get rid of much of their solid waste by coughing up pellets--which means that only the white stuff comes out their rear end.

This brings us back to "whitewash", as we birders call it. You can check around the bottoms of small conifer trees for large deposits of deposits. If it's pure white or cream colored, check the area above you for owls. If there are dark bits, you may have found the favorite perch of some other bird of prey. If the poop is purple or red, that probably means that a flock of robins or waxwings was perched overhead at some time.

Whenever you're looking for owls, one piece of advice holds true: FOLLOW THE CROWS.

Crows don't like owls. But they do like other crows. So when one of them finds an owl sitting in a tree, it'll start making lots of noise to get its friends to join in pestering the poor little owl. Eventually you end up with a flock of hundreds of crows circling one tree and constantly cawing. Whenever you see and hear this, go check out what they're so worked up over. It's not always an owl, but it will definitely be something big.

WHEN TO LOOK FOR OWLS:

The way to find owls activeduring the day is to go very early in the morning or very late in the evening. Especially in winter. Owls are forced to become crepuscular (active at dawn and dusk) or even diurnal at that time of year because none of the yummy little rodents come out at night if it's freezing outside. For late evening owls, I suggest coming to the Woodcock Walk at Meadowbrook Park in March--even though we're mostly looking for Scolopax americana, we usually see an owl or two as well.

WHERE TO LOOK FOR OWLS:

In general, owls prefer dense forest. Especially with conifers. In winter, however, many of them move to open areas like frozen-over marshes. If you can find the two habitats combined (such as in Sax Zim Bog in Minnesota or Muscatatuck National Wildlife Refuge in Indiana) then you have a good shot at finding owls.

Here are some of the best spots around here for owls:

Busey Woods: There's usually at least one Barred Owl in here at some time of the year. Northern Saw-Whet and Eastern Screech Owls are also possible.

Meadowbrook Park: Screech Owls and Great Horned Owls can be found on occasion. This is also the location of the Woodcock Walk in March.

Kickapoo State Park: The top location for Barred Owls in the area.

Clinton Lake: A good place to look for Northern Saw-Whet Owls, but you pretty much have to have an experienced birder with you who knows exactly where to look. Barred Owls are also found here.

If there's a really bad winter, Snowy Owls can be found in completely random places. If they're in the area, I'll let you know. But don't count on them showing up.

AND IF YOU CAN'T LOOK:

Owls are hard to see, but they aren't all that hard to hear. I've even heard a Barred Owl calling in my neighborhood. If you're going camping, wake up really early in the morning (4:00-5:00 or so) and listen for Barred Owls. They have a rather distinctive call.

To put in perspective how hard it is to find owls, here's my life total of owl sightings:

Barred Owl: 12+

Northern Saw-Whet Owl: 2

Eastern Screech Owl: 1

Unidentified: 2 (1 Great Horned or Long-Eared, 1 Barn or Short-Eared)

And here is my only photo of a wild owl:

This Barred Owl was at Muscatatuck National Wildlife Refuge in southern Indiana. I actually saw him several times, the first of which was using the FOLLOW THE CROWS method. The second time was pure luck, where he flew across the road as we were walking around looking for swans. The third time, when I got this picture, I was lucky to even notice him since he was just sitting there and not moving.

So chances of finding an owl by actively seeking them out are fairly low. They're more of something that shows up while you're looking for other birds. One of the other birders at the local Audubon Society says that for every 500 tree cavities he checks, only one has an owl in it.

Sorry if I just crushed anyone's dreams.

On the upside, there are plenty of other birds that you can see if you go birdwatching (hint, hint)

The results of the poll that I had up on the side of the blog last month indicate that readers like owls. So I'll write a post about watching owls.

To tell the truth, your best chance of finding owls is to go to the Anita Purves Nature Center and go see the Eastern Screech Owls they have inside. As for wild owls, things are a bit trickier.

The main problem with watching owls, of course, is that they are primarily nocturnal. It's very unlikely that you'll be able to see them when they're most active (I've actually seen two owls in the middle of the night: one flew under a streetlight and the other I identified based on its reflection on a moonlit pond as it flew overhead).

Don't despair, though! It is possible to see owls during the day.

But it's really hard.

HOW TO LOOK FOR OWLS:

One option is to try to find owls that are sleeping. Here are tricks for that:

1. Look in holes. Owls like to sleep in tree cavities or large birdhouses. Unfortunately, if the hole is big enough (like they prefer) they will not be visible from outside.

2. Check for "whitewash". Small owls often perch in the same tree many times. And while sitting there, they have to... well... do their business.

Time to learn about poop!

Unlike mammals, birds do not have separate liquid and solid waste. Instead, it all gets mixed up in the last stage of the bird's digestive tract. Solid waste is the little black or grey lumps. The white stuff that makes the wonderful little splats on the windshield of your car is the urine. Human urine packages the waste into the chemical urea, which is easy to synthesize but requires a lot of water to flush out of the excretory system. That's why human urine is clear. Birds, on the other hand, use the more complex chemical uric acid. Uric acid requires very little water to carry it out of the bird, so their urine is opaque and viscous.

Anyway, owls get rid of much of their solid waste by coughing up pellets--which means that only the white stuff comes out their rear end.

This brings us back to "whitewash", as we birders call it. You can check around the bottoms of small conifer trees for large deposits of deposits. If it's pure white or cream colored, check the area above you for owls. If there are dark bits, you may have found the favorite perch of some other bird of prey. If the poop is purple or red, that probably means that a flock of robins or waxwings was perched overhead at some time.

Whenever you're looking for owls, one piece of advice holds true: FOLLOW THE CROWS.

Crows don't like owls. But they do like other crows. So when one of them finds an owl sitting in a tree, it'll start making lots of noise to get its friends to join in pestering the poor little owl. Eventually you end up with a flock of hundreds of crows circling one tree and constantly cawing. Whenever you see and hear this, go check out what they're so worked up over. It's not always an owl, but it will definitely be something big.

WHEN TO LOOK FOR OWLS:

The way to find owls activeduring the day is to go very early in the morning or very late in the evening. Especially in winter. Owls are forced to become crepuscular (active at dawn and dusk) or even diurnal at that time of year because none of the yummy little rodents come out at night if it's freezing outside. For late evening owls, I suggest coming to the Woodcock Walk at Meadowbrook Park in March--even though we're mostly looking for Scolopax americana, we usually see an owl or two as well.

WHERE TO LOOK FOR OWLS:

In general, owls prefer dense forest. Especially with conifers. In winter, however, many of them move to open areas like frozen-over marshes. If you can find the two habitats combined (such as in Sax Zim Bog in Minnesota or Muscatatuck National Wildlife Refuge in Indiana) then you have a good shot at finding owls.

Here are some of the best spots around here for owls:

Busey Woods: There's usually at least one Barred Owl in here at some time of the year. Northern Saw-Whet and Eastern Screech Owls are also possible.

Meadowbrook Park: Screech Owls and Great Horned Owls can be found on occasion. This is also the location of the Woodcock Walk in March.

Kickapoo State Park: The top location for Barred Owls in the area.

Clinton Lake: A good place to look for Northern Saw-Whet Owls, but you pretty much have to have an experienced birder with you who knows exactly where to look. Barred Owls are also found here.

If there's a really bad winter, Snowy Owls can be found in completely random places. If they're in the area, I'll let you know. But don't count on them showing up.

AND IF YOU CAN'T LOOK:

Owls are hard to see, but they aren't all that hard to hear. I've even heard a Barred Owl calling in my neighborhood. If you're going camping, wake up really early in the morning (4:00-5:00 or so) and listen for Barred Owls. They have a rather distinctive call.

To put in perspective how hard it is to find owls, here's my life total of owl sightings:

Barred Owl: 12+

Northern Saw-Whet Owl: 2

Eastern Screech Owl: 1

Unidentified: 2 (1 Great Horned or Long-Eared, 1 Barn or Short-Eared)

And here is my only photo of a wild owl:

|

| Photo by the author |

So chances of finding an owl by actively seeking them out are fairly low. They're more of something that shows up while you're looking for other birds. One of the other birders at the local Audubon Society says that for every 500 tree cavities he checks, only one has an owl in it.

Sorry if I just crushed anyone's dreams.

On the upside, there are plenty of other birds that you can see if you go birdwatching (hint, hint)

What Is It? (Round 6)

We had great turnout for last week's ID challenge!

Last week's birds were Gambel's Quail (Callipepla gambelii) and Sora Rail (Porzana caronlina)

David mentioned that the Sora's body looked a bit strange... and he's right! For one thing, they have huge feet that spread their weight out over soft mud so they don't sink in. If that's not weird enough, they have muscles that let them flatten their own ribcages so they are less than an inch and a half wide. This lets them dart quickly through dense reeds (trust me, they are really fast).

So now it's time for Round 6!

These two are fairly easy. I figured I'd give you a week to relax before... THE COASTAL CHALLENGE!

Yeah, next week will be a big one. So start studying your seabirds.

Okay, back to Round 6.

Since you guys have been so great at identifying things quickly, I've decided to do at least two species per week.

Our first species here was out in a scrubby area near Lake Hodges in Escondido, California. Is he gorgeous, or what! (too bad the picture isn't all that great)

Since I was discussing owls and looking at birds in the dark, I figured I'd let you guys try some of that too (the dark part, not the owl part). You can't see much detail on this guy from San Antonio, Texas, but you can still identify him! Both pictures were taken at around 9:00pm outside the hotel I was staying in.

As usual, use the "view image" option to see these full size. Comments with answers are due by Thursday, November 8th. THE COASTAL CHALLENGE will open on November 9th (which just so happens to be my birthday).

Happy IDing!

Last week's birds were Gambel's Quail (Callipepla gambelii) and Sora Rail (Porzana caronlina)

David mentioned that the Sora's body looked a bit strange... and he's right! For one thing, they have huge feet that spread their weight out over soft mud so they don't sink in. If that's not weird enough, they have muscles that let them flatten their own ribcages so they are less than an inch and a half wide. This lets them dart quickly through dense reeds (trust me, they are really fast).

So now it's time for Round 6!

These two are fairly easy. I figured I'd give you a week to relax before... THE COASTAL CHALLENGE!

Yeah, next week will be a big one. So start studying your seabirds.

Okay, back to Round 6.

Since you guys have been so great at identifying things quickly, I've decided to do at least two species per week.

Our first species here was out in a scrubby area near Lake Hodges in Escondido, California. Is he gorgeous, or what! (too bad the picture isn't all that great)

|

| Photo by the author. |

|

| Photo by the author. |

|

| Photo by the author. |

Happy IDing!

Thursday, October 25, 2012

What Is It? (Round 5)

Note: make sure to read the post "Be Patient... Or Not" and try out the real-life birding challenge included there.

Congrats to Gloria and David on identifying last week's Yellow-rumped Warbler (and nice job considering subspecies)!

Note: If anyone needs a field guide during school hours, just ask me.

So now on to Round 5; We've got some fun ones this time... birds that are hard to see--and even harder to photograph! Camouflage, thick vegetation, and fast movement make the birds here tough to get a good view of, so you'll have to identify them on minimum amounts of information. As usual, I highly recommend that you use "view image" too see these photos full-size. Ready? Answers for both species are due by Halloween (that would be October 31st)!

Our first species was on a mountainside near Tucson, AZ. The first step is finding the birds!

The next three photos are all of the same bird in a marsh in South Padre Island, TX. The fact that it was evening and starting to get dark out didn't help my photography efforts.

My first attempt resulted in this: At least you can see its tail. Sort of.

Argh! Got the whole bird, but it's blurry...

There! It's in focus! Got it! Well, at least its rear end is. And it's really dark. Oh, well.

Trust me, there is enough information in these photos to identify both species.

Have fun!

Congrats to Gloria and David on identifying last week's Yellow-rumped Warbler (and nice job considering subspecies)!

Note: If anyone needs a field guide during school hours, just ask me.

So now on to Round 5; We've got some fun ones this time... birds that are hard to see--and even harder to photograph! Camouflage, thick vegetation, and fast movement make the birds here tough to get a good view of, so you'll have to identify them on minimum amounts of information. As usual, I highly recommend that you use "view image" too see these photos full-size. Ready? Answers for both species are due by Halloween (that would be October 31st)!

Our first species was on a mountainside near Tucson, AZ. The first step is finding the birds!

|

| Photo by the author. |

My first attempt resulted in this: At least you can see its tail. Sort of.

|

| Photo by the author. |

|

| Photo by the author. |

|

| Photo by the author. |

Have fun!

Wednesday, October 17, 2012

What Is It? (Round 4)

Two things of note to start off with:

1. Make sure to read the post "Be Patient... Or Not", which is an actual posty post and not one of these little ID challenges. It offers advice on how to see more birds if you have very little birding experience.

2. We've got a modifications to how "What Is It?" works: in order to be completely sure that everyone's' identifications are based off of their work and not just reading others' posts, once I see that you have commented with an answer I will mark it as "spam" and it will not be visible. Once that particular round of "What Is It?" is over, I will "unspam" all of the comments and they will be visible again.

Now with that out of the way,

Congrats to Gloria, David, Roberto, and Evan on their ID's of last week's Little Blue Heron (Egretta caerulea) and Tricolored Heron (Egretta tricolor)!

Once again, I will say that the Uni library has two bird field guides that you should make use of when trying to identify species. Also, I will have a field guide on hand during blog reading/writing days if you just can't be bothered to check one out from the library.

So on to round 4!

This bird is a bit less distinctive than last week's herons. Get used to it. I'll be kicking the difficulty level up another notch next time.

Anyway, this little guy was at a "water ranch" in Gilbert, Arizona in mid-March.

You have until October 24th to post an ID of this bird.

Have fun!

1. Make sure to read the post "Be Patient... Or Not", which is an actual posty post and not one of these little ID challenges. It offers advice on how to see more birds if you have very little birding experience.

2. We've got a modifications to how "What Is It?" works: in order to be completely sure that everyone's' identifications are based off of their work and not just reading others' posts, once I see that you have commented with an answer I will mark it as "spam" and it will not be visible. Once that particular round of "What Is It?" is over, I will "unspam" all of the comments and they will be visible again.

Now with that out of the way,

Congrats to Gloria, David, Roberto, and Evan on their ID's of last week's Little Blue Heron (Egretta caerulea) and Tricolored Heron (Egretta tricolor)!

Once again, I will say that the Uni library has two bird field guides that you should make use of when trying to identify species. Also, I will have a field guide on hand during blog reading/writing days if you just can't be bothered to check one out from the library.

So on to round 4!

This bird is a bit less distinctive than last week's herons. Get used to it. I'll be kicking the difficulty level up another notch next time.

|

| Photo by the author. |

You have until October 24th to post an ID of this bird.

Have fun!

Be Patient... Or Not.

One thing I hear a lot from people who I am trying to turn into birders is that they don't have enough time/patience/focus/whatever. I'll admit that in some ways this is a valid argument, especially for beginners. For someone with no prior birding experience, identification requires getting a really good look at the bird in question. For that to happen, you need the bird to sit out in the open, stay still for long enough for you to get your binoculars aimed at it, and show off some of its more definitive plumage patterns. Birds tend not to behave in such a way. If that's not bad enough, beginners haven't fine-tuned their vision to pick up on small bird-type movements (I'm really not sure how to describe this--there are just some things that look like the way a bird moves or the way the branches shake when a bird lands there), so they often notice fewer birds in the first place.

Since cooperative birds are so infrequent, it can take a long time for a beginning birder to find one. Thus quite a bit of time and patience are required if you want to start birding by yourself. Luckily, there are a number of remedies for this:

1. Choose your habitat wisely. Certain areas and environments make it just plain hard to see the birds that are there. Mature forests and dense underbrush may have thousands of warblers flitting to and fro, but you aren't likely to get a decent view of them when they're buried behind hundreds of leaves that are just as big as they are. The best habitat for beginner birders is, unfortunately, not one we have a lot of in central Illinois: marshes and other wetlands, the wetter the better. Go watch some ducks and herons. They're big, relatively slow-moving, and sit out in the water where they're easy to see. They can also be really interesting, especially if you catch some of them in the process of feeding. Also, while you're watching waterbirds, keep an eye out for anything unusual that might show up along the water's edge. You can check out the "Local Birding Sites" page of my blog to see recommendations as to where to go. As far as wetlands go, Curpros Pond is your best bet for good birding.

2. Put up birdfeeders! These provide excellent viewing opportunities of backyard birds like cardinals, sparrows, finches, and doves. Try to have a variety of the kinds of food that you offer. Seed mixes often have a list of birds they are specific to, but anything with sunflower seeds is a good bet for the majority of species. Goldfinches love "sock feeders" with small thistle-type seeds. In winter, considering putting out suet cakes (solid beef fat often combined with seeds and mealworms) and whole peanuts to attract woodpeckers, nuthatches, blue jays, and, depending on where you live, chickadees and titmice. In general, birds are more attracted to feeders in winter because food is scarce elsewhere.

3. Go birding with someone who has lots of experience! "Serious" birders can point out birds and identification features that you would otherwise miss, and often know exactly where to look for certain species. I used to be a raw beginner, but the local Audubon Society has raised me well. Keep an eye out for any of my email announcements of birding events, and consider attending a few Audubon Society birdwalks, the last two of which for this year will be from 7:30-9:00 starting at the Anita Purves Nature Center in Urbana on October 21 and October 28.

4. Practice! One thing I can't stress enough is that birding gets more exciting the better you are at it. Most of all, learn how to aim binoculars quickly and accurately. Once you can do that, you'll start getting really good views of birds that don't sit still very long, notably warblers.

Aaaand, just as some encouragement, I have a little challenge. Go birding somewhere (anywhere, even your own backyard) for 15-30 minutes, and keep track of all the species you see. Post a comment with where you went and a list of species you saw. How many can you find?

Oh, and photos are welcome, too. Especially if you're not quite sure what kind of bird it is.

Happy birding!

Since cooperative birds are so infrequent, it can take a long time for a beginning birder to find one. Thus quite a bit of time and patience are required if you want to start birding by yourself. Luckily, there are a number of remedies for this:

1. Choose your habitat wisely. Certain areas and environments make it just plain hard to see the birds that are there. Mature forests and dense underbrush may have thousands of warblers flitting to and fro, but you aren't likely to get a decent view of them when they're buried behind hundreds of leaves that are just as big as they are. The best habitat for beginner birders is, unfortunately, not one we have a lot of in central Illinois: marshes and other wetlands, the wetter the better. Go watch some ducks and herons. They're big, relatively slow-moving, and sit out in the water where they're easy to see. They can also be really interesting, especially if you catch some of them in the process of feeding. Also, while you're watching waterbirds, keep an eye out for anything unusual that might show up along the water's edge. You can check out the "Local Birding Sites" page of my blog to see recommendations as to where to go. As far as wetlands go, Curpros Pond is your best bet for good birding.

2. Put up birdfeeders! These provide excellent viewing opportunities of backyard birds like cardinals, sparrows, finches, and doves. Try to have a variety of the kinds of food that you offer. Seed mixes often have a list of birds they are specific to, but anything with sunflower seeds is a good bet for the majority of species. Goldfinches love "sock feeders" with small thistle-type seeds. In winter, considering putting out suet cakes (solid beef fat often combined with seeds and mealworms) and whole peanuts to attract woodpeckers, nuthatches, blue jays, and, depending on where you live, chickadees and titmice. In general, birds are more attracted to feeders in winter because food is scarce elsewhere.

3. Go birding with someone who has lots of experience! "Serious" birders can point out birds and identification features that you would otherwise miss, and often know exactly where to look for certain species. I used to be a raw beginner, but the local Audubon Society has raised me well. Keep an eye out for any of my email announcements of birding events, and consider attending a few Audubon Society birdwalks, the last two of which for this year will be from 7:30-9:00 starting at the Anita Purves Nature Center in Urbana on October 21 and October 28.

4. Practice! One thing I can't stress enough is that birding gets more exciting the better you are at it. Most of all, learn how to aim binoculars quickly and accurately. Once you can do that, you'll start getting really good views of birds that don't sit still very long, notably warblers.

Aaaand, just as some encouragement, I have a little challenge. Go birding somewhere (anywhere, even your own backyard) for 15-30 minutes, and keep track of all the species you see. Post a comment with where you went and a list of species you saw. How many can you find?

Oh, and photos are welcome, too. Especially if you're not quite sure what kind of bird it is.

Happy birding!

Monday, October 8, 2012

What Is It? (Round 3)

Okay, I'll confess that Round 2 may have been a bit challenging. However, Gloria and Roberto both correctly identified the pair of Double-Crested Cormorants (Phalacrocorax auritus). I let it slide this time, but from now on it's your most recent answer that counts when I tally up the score at the end. Interestingly enough, there actually was a Neotropic Cormorant at Horicon while I was there a few years back, but these two are too big and not skinny enough to be the Neotropic (plus, there was only one Neotropic there).

No one correctly identified the third bird, but this one was especially hard for a number of reasons:

1: The photo doesn't show all that much detail

2: The bird is a juvenile.

3: It is a migratory raptor, and thus some range maps don't show it inhabiting Wisconsin

4: There are three different subspecies of this bird in the US, and they don't all look the same,

4.5: and this guy/gal is not of the most common subspecies.

We had some guesses of Northern Harrier, which isn't half bad since this bird's color, speckling, and banded tail match that of a female Circus cyaneus. It's in the right habitat and location, too. It's even the right size. But it's not a harrier. I'll walk you through the identification:

Everyone seemed to get that it was a bird of prey based on its size and shape. After that, the most important identification feature of this bird is the face. Notice the really dark vertical stripe below the eye and the large white patch behind it. Harriers don't have facial patters as bold as that. That area of dark feathers is called a malar or moustachial stripe. This feature rules out all of the North American raptors except for falcons. Based on its size (approximated by comparing it to the cormorants) it has to be either Prairie, Peregrine, or Gyrfalcon. A gyr would be too dark and would not show up in Wisconsin unless it was a really bad winter and there wasn't enough food up north. This bird's color points towards Prairie Falcon... BUT WAIT!

The malar stripe is too large and dark for Prairie Falcon. And what would it be doing in the middle of a huge marsh? They eat mainly ground squirrels--which you aren't likely to find swimming. Horicon Marsh has lots and lots of waterfowl, which are perfect food for...

Peregrine Falcons!

Yup, this bird belongs to the fastest species on the planet. To be specific, this is a juvenile of the subspecies Falco peregrinus tundrius who was migrating south for the winter and happened to stop by in Wisconsin.

Okay, after all that... We move on to Round Three!!!

It's two species again, but this time you only have until October 15th to identify both... so start now!